Part 2 No. 1 (Previously on Unsettled)

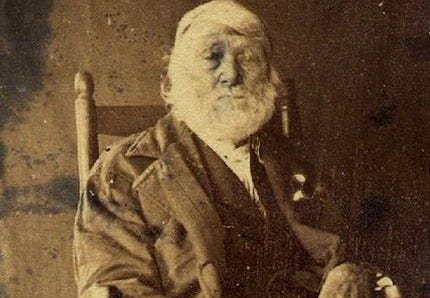

I have 32 great-great-great-great-grandfathers. Everyone does. Imagine if you could go back to the mid-1800s and visit with just one, let’s say Pvt. Adam Link, the oldest living Revolutionary War soldier. By then, his beard would have been gray and his memory foggy, but the old soldier still would have been up to an afternoon visit and a chance to talk about the war. The two of you would settle on his wood-planked porch shaded at one end by a curtain of honeysuckle.The old man would sit back in his rocking chair, take a swig of strong coffee, and retell his story one more time.

Reality

An imaginary conversation, however, makes for unreliable history. What I’m after is a story that’s true—a story about my old grandfather, a story of one who really did fight in the Revolutionary War. Building a story based on facts is not as easy as listening to a fanciful story on the front porch. Facts are history’s backbone, and if there aren’t enough to put meat on those bones, there’s no story. The only way to know that is to do the research. It’s a tedious process that involves digging through records, uncovering the facts and determining their worth in supporting the story. While conducting research is often the fun part of history, it also can be a great waste of time. Research is serious business though and requires as much organization and discipline as any other day’s work.

The only visual records of the war were illustrations depicting either famous figures or the drama of the battlefield. Photography wouldn’t come into use until half a century after the war ended. A handful of weekly newspapers, published as single-sheets, rarely reported detailed accounts of the war. The most influential sources during that time were simple, one-page pamphlets that were easily printed and widely distributed. The thinkers and political leaders of the time—Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin,Thomas Paine, Patrick Henry, and James Madison—all wrote pamphlets to express and disseminate their ideas and opinions. These editorial pieces were critical in building support for the revolution. However, I cannot claim a single one of these illustrious men as an ancestor.

The search begins…

At a long-ago family reunion an aunt gave me a copy of the McKinzie family history. The McKinzies were a tough bunch out of Georgia who settled in Texas in the 1850s. On one page, I found a hand-drawn family tree that listed family names and dates, but little else. Years went by before I would return to that old tree but when I did, I landed in the age of computers. (In 1983 we bought one of the first personal computers, an Apple IIe. I still have a Mac.) When Ancestry Publishing launched ancestry.com, I was one of the first members. With the help of technology, and that faded family tree, I was able to track down my own old soldiers.

Still, I was in search of that one grandfather, the one with enough meat to make one good story. Personal accounts of the war, however, were written mostly by high ranking officers, officials or educated observers. Of the war in the field, soldiers were left to write of their own experiences in the battlefield or in Washington’s winter camp. The foot soldier rarely contributed to the historical record, primarily because not many could read or write, let alone be afforded the time to keep a diary. The rare exception was Joseph Plumb Martin’s (no relation) memoir. Martin, the son of a Yale-trained minister, interrupted his own education at age 15 to join the army. He kept a diary during the entire eight years he was in the army. Although he wrote his memoir when he was 70 years old, his writing captures his young soldier’s voice.

Here [Fort Mifflin] I endured hardships sufficient to kill half a dozen horses. Let the reader only consider for a moment and he will still be satisfied if not sickened. In the cold month of November, without provisions, without clothing, not a scrap of either shoes or stockings to my feet or legs, and in this condition to endure a siege in such a place as that was appalling in the highest degree.

After the battle at Yorktown, however, he wrote of feeling “a secret pride swell my heart when I saw the ‘star-spangled banner’ waving majestically in the very faces of our implacable adversaries.”

Except for Martin’s memoir, most of what we know of these soldiers comes from their military records. These official accounts list the soldier by name, regiment and in some cases the names of the battles in which they fought. It is these records that provided the first evidence that one of my ancestors fought in the War of Independence.

Additional details of a soldier’s wartime service were collected after the fact. The Continental Congress passed the 1776 Pension Act with the intent of rewarding soldiers for their service in the war. However, from the beginning of the war to the end, the government treasury never had the money to pay pensions. At first it could only fund pensions for officers and disabled soldiers. Meanwhile, thousands of rank and file soldiers would have to wait until the government treasury was more solvent. Their pensions were’t paid until long after the war ended. Due to the delay and gaps in record-keeping, each soldier was required to provide proof of military service to receive his benefits. Fortunately, the belated documentation provided more detailed information of the veteran’s service and would be a gold mine for researchers and amateur historians alike.

Promises, promises

The new government had entered the war with barely enough money in its treasury to pay its soldiers. But the army could promise recruits a pension and free land if they served until the war was over. While the treasury was thin, the government had plenty of public land to offer. The government used the grants not only as a recruiting tool, it also hoped the offer of free land would encourage settlement. Depending upon their rank, officers were to receive 500 to 1,100 acres, with privates and non-commissioned officers entitled to 100 acres each.

While land grants were a windfall for veterans, the practice devastated the Native American tribes, who originally possessed these lands. After the army defeated the tribes in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, by treaty the government acquired 61 million acres of land in northwest Ohio. By 1855, the federal government had issued 500,000 grants for these lands.

By the time the government could pay out the promised benefits, many veterans had already died, while the rest were seventy years old or older. (Life expectancy in eighteenth-century America was between forty-one and forty-seven years.) So much time had passed that many of the soldiers’ records were lost or the men couldn’t remember crucial facts about their service. A widows applying for benefits not only had to provide proof of their late husband’s service, she had to show proof of their marriage. Many a widow’s claim was rejected because she didn’t have the proper documentation.

In addition to government records, the files of organizations such as the Sons of the American Revolution also contain records pertaining to war veterans. To become a member of the group, an applicant must be a direct descendant of the soldier and provide proof of his Revolutionary War service.

Martin and Murphy

A search through records like these unearthed the names of several of my 4th great-grandfathers who served during the Revolutionary War. They include Sgt. Charles Davis, who served in Maryland’s 12th Battalion, and an uncle William Graham who fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain and was a signer of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence of North Carolina. The names of two other soldiers caught my eye, first because I recognized their family names, and second because their files were full of information. I had enough to tell one, possibly two good stories.

Pvt. Richard Martin and Pvt. James Murphy both marched in Washington’s army and both fought with the general at the battles of Germantown and Monmouth. Although they both served in the 4th regiment, there is no record that they knew each other. The Martins were landowners and slaveholders in South Carolina while the Murphys were city folk from Baltimore. But they did share a singular time and place in the nation’s history as well as in my family’s. Both possessed a restless nature that led generation after generation to settle lands ever westward.

To come: The life and times of Martin and Murphy

Notes

Bailyn, Bernard and Jane N. Garrett, Eds. Pamphlets of the American Revolution, 1750-1776, Volume I: 1750–1765. Harvard University Press.

Graves, Will, Transcribed. Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters. Revised June 20, 2016.

https://sc-art.org/collection/southern-campaigns-revolutionary-war-pension-statements-rosters/

Paine, Thomas. Common Sense, The Crisis, and Other Writings from the American Revolution, (Paperback Classic)

U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Object 2: Bounty Land Warrant, “History of VA in 100 Objects,” Jan. 7, 2022. https://department.va.gov/history/100-objects/object-2-bounty-land-warrant/

Warren Jack D., Jr., “Joseph Plumb Martin, Everyman.” American Revolution Institute of the Society of Cincinnati, Feb. 20, 2020. https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Blog-PDF-Joseph-Plumb-Martin-Everyman.docx

Linda- I like the idea that these two people “share a singular time” in history. I appreciate the depth and perception.